Wildflower Meadows: Let’s Get Real

Americans use enormous quantities of water, fuel, fertilizers, and pesticides to make lawn grow vigorously, only to then spend time and money weekly to keep it short. So why, even amidst growing ecological awareness, do lawns continue to dominate our landscapes? Some reasons for lawns make sense, but lack of practical alternatives may be a major cause. If we’re ever to be weaned from over-reliance on lawns, dependable, cost effective solutions must be available.

Why have wildflower meadows not become a staple of the American landscape? Designed meadows have been available for years and have received great amounts of publicity. Claims that they can provide a carpet of beautiful flowers, with little or no maintenance would seem to make them an ideal solution. They have not proliferated because all too often they have failed. Deficient seed mixes and poor planning have caused too many of these projects to be one year success stories which end with a massive weed invasion and a showing of the familiar horror flick, “Return of the Giant Mower”. In some cases they have failed because the expectations generated have been so unrealistic that even a success can seem to be a failure. All of this has done more harm than good, as much of the inclination and energy for change on the part of the public has been squandered.

Photo by Ian Caton

In fact, wildflower meadows, if planned, installed and managed properly, can contribute tremendously to naturalizing the American Landscape. When integrated into a well-designed landscape matrix, a meadow can help transform a residential property into a beautiful and stimulating home environment while vastly reducing quality time with a noisy mower. Large corporations can dramatically reduce maintenance costs, as has been documented on numerous projects, and public highways and parks can enhance our spectacular and diverse native landscape on a visual and ecological level.

Before we begin to discuss how to obtain these results, we need to clarify what we mean by a native wildflower meadow and how it differs from the one-year wonders we have previously described. In order to fulfill the requirements of long term sustainability and low maintenance, the meadow must be designed as a functional plant community first and a flower garden second. Only by understanding and incorporating the compositions, patterns and processes inherent in our naturally occurring meadows and prairies can we create landscapes that will be viable over long periods of time without massive amounts of assistance.

Does this mean that we must sacrifice aesthetics for sustainability?

Not at all. True, we won’t see a wall-to-wall carpet of colors as is commonly depicted on wildflower seed packets, but we need not lower expectations, only change them. A visual foundation of native ornamental grasses glimmering in the sun and swaying in the breeze, complemented by graceful drifts of wildflowers will provide a truly spectacular scene, more inspiring and certainly more sustainable than the riot of color depicted on the seed packet. Instead of waiting in dread to see what will emerge the second year after the annual flowers have expired, we can enjoy an ever evolving natural landscape that changes from season to season, and year to year as it reflects the beauty and grace of our native meadows and prairies.

Photo by Ian Caton

Sounds very nice, right, but how do we get it done? While we are waxing poetic the weeds have something else in mind. The following are some of the most important elements for designing, implementing and managing a native meadow that we can feel confident will fulfill our expectations.

SITE ANALYSIS

Analysis of the site will be the first order of business and there are four main aspects to be considered.

Item number one is light exposure. Full sun is a necessary requirement for a meadow planting. Insufficient sunlight will favor woody species over herbaceous wildflowers and grasses causing an increase in maintenance requirements.

Soil type will be your next consideration. It is imperative to understand and identify which soil you are working with (sand, loam, clay, etc.) in order to select plants that will adapt successfully to the site. If poor soils exist, a decision can be made to either amend the soil or narrow the plant list to those that will tolerate that specific condition. In some cases bad soil conditions, either poorly drained or very dry, can provide a competitive advantage to the meadow species. Many of the most notorious weeds favor richer soils while there are numerous native flowers and grasses that thrive in poor conditions. Plants with strong ornamental characteristics such as Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa) and Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) will grow well in dry sands while Pink Turtlehead (Chelone lyonii) and New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) will thrive and flower in poorly drained clay soils.

Asclepias tuberosa and Pycnanthemum tenuifolium

High soil nutrient levels will be less important than in traditional landscapes as most native plants are generally adapted to existing conditions. Barring an extreme deficiency, fertilization should be avoided as it will probably favor the weeds more than the desirable species.

Grade and topography can effect a number of decisions to be made in planning the meadow. A north slope may not be favorable to meadow plants as they will receive less direct sunlight. If the meadow is in a low lying area and remains wet during spring thaw and rains, plants adaptable to these conditions should be selected. A sloped site may favor spring as opposed to late fall seeding to avoid washing of un-germinated, dormant seed during winter. Also micro variations within the site can be noted and considered in the plant selection and placement process in order to further match the plant to its proper environment.

Analyzing existing growth on and adjacent to the site can yield extremely valuable information relating to what plants will grow well on the site and what specific weedy species are likely to be a problem. If a problematic weed is existing on or near the site it is highly recommended to eradicate it beforehand in order to avoid future infestations.

SEED MIX COMPOSITION

Based on your analysis of the site, you can now select the plant species that will comprise your seed mix. The plants that will afford the best long term results will invariably be those that are found in conditions similar to your site and are native to your particular region. Although the temptation is great to include showy exotic species selected for their floral characteristics, their likelihood of survival is far lower. While plants which are marginally adapted to a site can often survive in a cultivated garden where competitors are eliminated through weeding, mulches and fabrics, in a highly competitive meadow planting only the most adapted vigorous plants will survive.

As in most naturally occurring meadows and prairies, grasses should be a major component of the plant mix. They are the single most important component in stabilizing the meadow from both a functional and visual point of view. Only clump forming grasses should be used including Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans), and Purple Lovegrass (Eragrostis spectabilis). A nurse crop usually composed of a fast germinating, clump forming grasses such as Canada Rye or Common Oats should also be included to help secure the site from weed invasion and erosion during the first season. This is very important. The initial phase is the most volatile as the longer lived perennials and grasses are not yet well enough established to control the site.

An important concept to understand when combining plant species is the concept of niche. A study of a mature Midwestern prairie will reveal an incredibly dense tapestry where every possible space is occupied. A tiny section of five foot prairie will contain a canopy, numerous mid layers and a creeping understory. Mat forming root systems occupy the upper soil layers while deep fibrous and tap roots hold down the fort below. If all of these elements are present the meadow will have a strong capability to resist weeds. There is no place left for them to grow.

In addition to filling the various niches in space, you need to fill the niches in time. (Don’t worry, I’m not getting weird on you. I have something concrete in mind). First is seasonal time. Some plants are active in warm weather while some plants are most vigorous during the cool seasons, particularly spring. By including both types there will be no seasonal opening for weed invasion. A second type of niche relating to time is measured in years. Some plants establish a cover during the first year, some during the first few years and some long lived plants may not have a serious presence for many years. All of these need to be present to avoid a weak stage in the meadow’s competitive ability.

Variation in cool season and warm season growth across the growing season

Unfortunately the vast majority of seed mixes on the market have given little or no thought to any of these functional considerations. They are mostly composed of annuals, biennials and short lived perennials that are selected for quick results at a cheap price. It is very unlikely that they will last more than a year or two. If you put Flax, Poppies and Cosmos in the ring with Canada Thistle, Japanese Honeysuckle and Oriental Bittersweet it’s not hard to guess who will be left standing after the last round. You need a far meaner crew than that to stand up to those neighborhood bullies. Even the all perennial mixes sometimes offered do not usually include sufficient long term species to make the planting competitive beyond the early stages. In other words there are perennials and there are perennials.

Why is it so difficult to find a seed mix that provides the plants needed for the long haul? The answer can be found in an examination of the different reproductive characteristics of long and short lived herbaceous plants. Annuals, biennials and short lived perennials produce large amounts of flowers and seed early in life as a proliferation strategy, compensating for the fact that they won’t be alive very long. This makes their seed cheap to produce and their floral impact immediate. Long lived perennials on the other hand, planning to stick around through good times and bad, are more interested in expending their energy on early vegetative growth to gain a foothold amongst the competition. Flower and seed production is a low priority at this early stage. The bad news here is that a seed mix designed for the long term makes two years to produce flowers and will inevitably cost more. The good news is that you won’t get stomach cramps every time you receive a phone message from your two and three year old meadow clients.

Established meadow with dense, diverse growth

There is still one more item on the seed mix wish list. Even if the seed composition contains sufficient long term, competitive plants to produce a sustainable meadow, these mixes need to be available not only according geographical region (northeast, Midwest, etc.), but by soil preference. It makes no sense to spend time determining that you have a poorly drained site containing a heavy clay soil and utilize a mix in which half of the plants are native to dry sandy conditions. Meadow mixes formulated for dry, mesic, and wet soil conditions, composed of plants native to the particular region will undoubtedly serve as the best possible foundation for a successful and efficient mix.

The best route to take however is to order seed by individual species. You can further fine tune the site adaptability of your plant composition and segregate species according to micro areas within the site. There are a growing number of suppliers that offer native perennials and grasses in this form and expert advice is often an additional bonus. Individual species selection can also allow for additional design flexibility regarding the aesthetic aspects of the meadow. Consideration can include combinations of flower color and forms, foliage textures and succession of bloom as in any well planned landscape garden.

In addition, plants to encourage wildlife can be included, adding another dimension to the enjoyment of the landscape. The seed heads of many of the grasses and wildflowers will attract birds to the meadow (Liatris, Rudbeckia), particularly in winter, while a number of meadow plants are particularly attractive to Hummingbirds (Lobelia, Monarda, Penstemon).

Monarda seed heads in a Schizachyrium scoparium meadow

In regards to installation of the meadow, much of the process is similar to turf grass seeding. Creating a finely graded seed bed, incorporating the seed into the soil, tamping or rolling for good seed to soil contact and mulching with salt marsh hay or a clean straw is necessary. Timing can be slightly different. Sowing in the fall is limited to late dormant seeding and the spring seeding period can extend into early summer. Late fall sowing is not recommended on sloped sites where erosion can be a problem.

Site preparation will be of the utmost importance in achieving a successful meadow. It begins with the elimination of existing growth. The most common methods are several repeated applications of short lived herbicide, repeated tilling or a combination of the two. Tilling will bring to the surface dormant weed seeds which must be allowed to germinate and then shallowly cultivated or sprayed with herbicide before planting. This can be avoided with a no-till seeding if a shallow seed bed can be worked up among the dead plant material.

A site prepared for seeding

DISTRIBUTING THE SEED

Due to the small seeding rates of the perennial flowers and some of the grasses it will be necessary to mix the seed with an inert material (sawdust, sand etc.) before spreading. Arrangement of plants in the meadow is best done by combining the designer’s creativity with the patterns that occur in nature. Naturally occurring meadows rarely have a homogeneous mix of species evenly scattered throughout the area. More commonly, an individual plant or plant group, usually including grasses, will dominate, with smaller colonies of plants occurring in pockets or drifts. Replicating this arrangement can yield a natural and appealing meadow which relies more on the form and textures of grasses interplaying with subtle touches of color, than a difficult to obtain constant explosion of bloom.

Seed mixed with a carrier and ready for hand spreading

Sometimes small pockets of an isolated species can correspond to a micro condition on the site such as a low moist area. By following the lay of the land in placement of plants or plant groups, you not only increase survivability of those plants, but create a landscape that automatically appears natural and graceful.

Seeding specialty overlay mixes by hand

Meandering paths and secluded sitting areas can be seeded with low grasses and spring ephemeral flowers (Bluets: Houstonia caerulea, Violets: Viola species) to be occasionally mowed during the season for easy access. This can allow the sights, smells and sounds of the landscape to be appreciated from within, adding an experiential element to the planting. The lines where meadow meets mowed lawn can become an additional feature of the landscape creating a graceful transition from the controlled to the wild landscape.

POST PLANTING MANAGEMENT

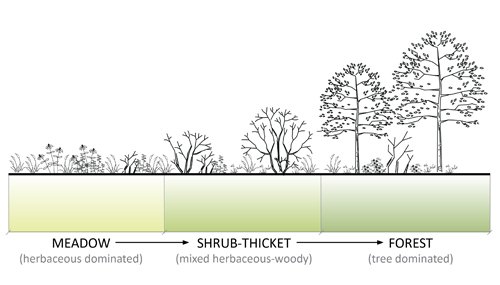

An understanding of ‘ecological succession’ will be extremely important for the maintenance of the meadow. This is the process by which a disturbed area progresses naturally from herbaceous meadow (first annuals then perennials) to woody shrubs and pioneer trees and finally to a mature forest. In dry portions of the country various forms of prairie are the mature stage of the process. In establishing a permanent meadow where woods naturally predominate we are arresting the process of ecological development at the herbaceous perennial stage. By understanding nature’s next ‘move’ throughout the process we are better able to make intelligent decisions resulting in less maintenance requirements and a more successful end result.

Stages of succession from meadow to shrub-thicket to forest

Also the client must understand that although their meadow, once established, will require substantially less maintenance than mowed lawn once established, the first one to two years will require guidance in order to achieve successful results. A maintenance plan should be in place before starting, to ensure that this crucial portion of the project is not later neglected.

After planting, it will be necessary to carry out a weed control program to ensure the successful establishment of the meadow. The methods that will be most appropriate will be determined by the size of the project, maintenance budget, method of installation and what weed species appear. As the process of ecological succession would suggest, the first year will bring a rapid cover of annual weeds while the perennial wildflowers and grasses are slowly developing underneath.. This is to be expected, and if managed properly, is not a problem.

By mowing the meadow every 6 weeks to a height of 4-6″, you will not only prevent the annual weeds from seeding, but ensure that the young perennial plants growing below your mow height receive enough light for strong establishment. These perennials will emerge the following year far stronger than if they had been buried under 4 feet of annual foliage the first year. This is why the inclusion of annual wildflowers in your seed mix can be detrimental to the long term health of the planting. Annual wildflowers are included for their ability to bloom the first year. In order for this to occur you will be prohibited from mowing, this will allow annual weeds to go unchecked and deprive the emerging perennials of the light needed for optimal growth.

First year meadow growth (annual cover crop and meadow seedlings)

During the second year the faster growing perennials (such as Black Eyed Susan: Rudbeckia hirta, Purple Coneflower: Echinacea purpurea, and Bee Balm: Monarda fistulosa) will begin to provide color and the entire planting should be well enough established to allow a decrease in weed control. You will need to monitor the planting for those weeds that can cause problems for the meadow. If needed, control can be obtained through spot herbicide application, manual weeding, or an additional mowing/cutting during the most active growth period of the problem weed.

Meadow in third-to-fourth year

By the third year the native meadow plants should be fairly dominant on the site and able to resist weed invasion with minimal management. Maintenance will consist of periodic monitoring and one mowing or burn either in the late winter or early spring.

Annual late winter/early spring mowing

Once established, the native meadow planting exemplifies the blending of horticulture, design, and ecology and results in an easily managed, ecologically sound and visually dynamic landscape to be enjoyed for years to come.

The current trend toward ecological concern, economy, and appreciation of the natural world has created a public eager for new ways to incorporate nature into their homes, businesses and public lands. Native meadow and prairie plantings blend perfectly with these emerging attitudes, presenting an outstanding opportunity for those landscape designers, architects and planners who have made an effort to understand the ecological principles needed for their successful design and implementation.

Recommended Perennial Wildflowers for Northeastern Meadows

(D=dry, M=mesic, W=wet)

Asclepias tuberosa: Butterfly Weed | D, M

Symphyotrichum novae-angliae: New England Aster | M, W

Baptisia species: False Indigo | M, D

Boltonia asteroides: Thousand Flowered Aster | D, M

Chelone glabra: Pink Turtlehead | M, W

Chrysanthemum leucanthemum: Oxe Eye Daisy | D, M

Coreopsis lanceolata: Lance Leaf Coreopsis | D, M

Echinacea purpurea: Purple Coneflower | D, M

Eupatorium fistulosum: Joe Pye Weed | M, W

Filipendula rubra: Queen of the Prairie | M, W

Iris versicolor: Blue Flag Iris | W

Liatris species: Blazingstar | D, M, W

Lobelia cardinalis: Cardinal Flower | M, W

Lobelia siphilitca: Blue Lobelia | M, W

Mimulus ringens: Monkey Flower | W

Monarda fistulosa: Bergamot | D, M

Penstemon species: Beardtongue | D, M

Ratibida pinnata: Yellow Coneflower | D, M, W

Rudbeckia hirta: Black Eye Susan (self seeding biennial) | D, M

Solidago species: Goldenrod | D, M, W (Do not use Solidago canadensis, which, while it is native, is highly vigorous and tends to overwhelm desired vegetation.)

Tradescantia ohiensis: Spiderwort | D, M

Vernonia novaboracensis: Ironweed | M, W

Recommended Grasses for Northeastern Meadows

Andropogon gerardii: Big Bluestem | D, M

Bouteloua curtipendula: Sideoats Grama | D, M

Panicum virgatum: Switch Grass | M, W (live plants only as tends to form monocultures when planted from seed)

Schizacharium scoparium: Little Bluestem | D, M

Sorghastrum nutans: Indian Grass | D, M (live plants only as tends to form monocultures when planted from seed)

Elymus canadensis: Canada Wild Rye | D, M, W

Common Problem Weeds in Northeastern Meadows

Artemisia vulgaris: Mugwort

Cirsium arvense: Canada Thistle

Celastrus orbiculatus: Oriental Bittersweet

Lonicera japonica: Japanese Honeysuckle

Lythrum salicaria: Loosestrife (wet meadows)

Rosa multiflora: Multiflora Rose

Originally published in Landscape Design, Jan. 1996. Photos by Larry Weaner unless indicated otherwise.